Over a period of more than a hundred years, Josef Mueller and his son-in-law Jean Paul Barbier-Mueller, each driven by an ardent curiosity and gifted with an infallible eye, assembled the largest collection in private hands of traditional arts of Africa, Asia, Oceania, pre-Columbian America and various ancient civilizations. Forty-seven years ago, in 1977, Monique and Jean Paul Barbier-Mueller founded a museum in Geneva to share this collection with the public; it includes a great number of must-see masterpieces.

A Hundred Year Old Family Collection

Josef Mueller

Josef Mueller was born in 1887 into a middle-class family from Solothurn, in German-speaking Switzerland. Nothing predestined his becoming one of the greatest art collectors of all time. At the age of six, he lost both his father and his mother, and was raised by a governess. However, he had the chance to frequently visit the home of one of his schoolmates, whose parents were lovers of modern art and who introduced him to art.

In 1907 at 20 years old, he spent a whole year’s income on one painting by Ferdinand Hodler. Then he swiftly made his way to Paris where he met the famous art dealer, Ambroise Vollard. Acting on the advice of the latter, he acquired a highly renowned painting by Cézanne, The Jardinier Vallier, painted in 1905, at the very end of the future father of modern painting’s life. Josef Mueller put together a collection with extraordinary rapidity that, as early as 1918, included several works by Cézanne, by Matisse and by Renoir, without counting the Picassos, the Braques and as many other paintings by prestigious masters.

The thirst for novelty and the desire (formulated by Rimbaud) to be “absolutely modern” drove artists to explore the unknown. In the wake of the Impressionists’ revolutionary innovations, the Fauvists (Derain, Vlaminck, Matisse) were the first to realise that African fetishes, whose seeming crudeness had previously been cause for derision, could find a place among works of art that spring from man’s natural creative impulse and his endless quest for formal perfection.

In the 1920s, a handful of enthusiastic artists and collectors were delighted to discover both the ingenuity and the honesty of the designs of tribal artists who, oblivious to the notion of art for art’s sake, produced works not of personal expression, nor to please a public of connoisseurs, but as an essential part of their magical and religious beliefs, which sought to maintain a balance between the contradictory forces that operate in the world.

In 1935, the New York Museum of Modern Art organised a large exhibition entitled African Negro Art. All the works on display were owned by Europeans, among them the poet Tristan Tzara, who possessed a magnificent Gabonese mask which the Musée Barbier-Mueller was to acquire in1988.

Josef Mueller did not contribute anything to this exhibition; in fact, he rarely participated in public events. He would most certainly have refused to hold a conference or to explain the reasons behind the accumulation of so many treasures. However, in 1957, at the age of seventy, Mueller decided to exhibit his African collection in the museum of his native town, Solothurn, where he had returned to live after the war.

abm-archives barbier-mueller.

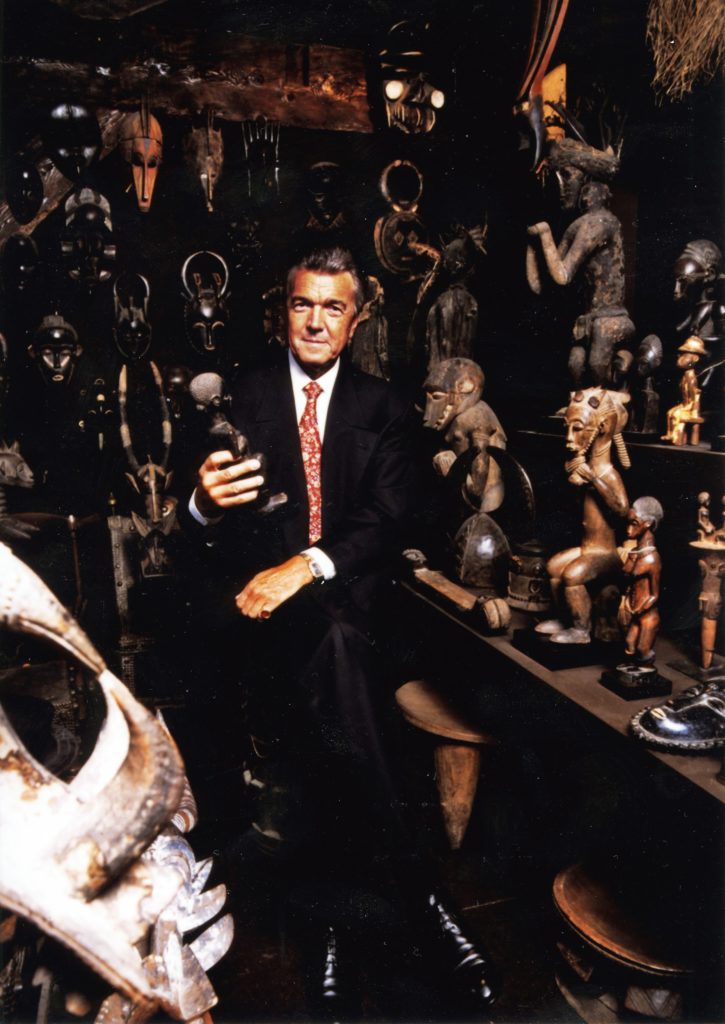

Jean Paul Barbier-Mueller

In 1952 Jean Paul Barbier became engaged to Josef Mueller’s daughter, Monique, whom he married in 1955. At Josef Mueller’s home, Jean Paul Barbier discovered non-Western arts. Himself a collector of original editions of books from the Renaissance and objects of classical antiquity and from the Eurasian Steppe, he actively began to bring together his own sets of works. As Josef Mueller continued to enrich his collection of African art, Jean Paul Barbier-Mueller concentrated more on the arts of Oceania and Island Southeast Asia.

As a historian and art lover, Jean Paul Barbier understood Josef Mueller’s irritation that the works of so-called “primitive” art remained defiantly underestimated while his other paintings received copious praise. Perhaps it was at this moment that the idea of a permanent museum of primitive art was conceived; an idea that would come into effect twenty years later, in Geneva, where Monique and Jean Paul Barbier-Mueller were to settle.

1977

The Musée Barbier-Mueller opened its doors in May, 1977, three months after Josef Mueller’s passing. Many friends of the family, art lovers and connoisseurs from all over the world took part in this event. They soon joined together to form the Friends of the Musée Barbier-Mueller Association, which today consists of nearly one thousand members.

abm-archives barbier-mueller.

The Musée Barbier-Mueller in Geneva

In founding the Musée Barbier-Mueller in 1977, Jean Paul Barbier-Mueller wanted to share with the public his passion for the traditional arts. He expended all his energy and devoted considerable time and money to ensure that the museum’s collections would be studied by the best specialists and would be exhibited and published. He sought to make known and encourage recognition for the non-Western arts, in Switzerland but also internationally, with itinerant exhibitions, loans to various museums throughout the world, and the founding of Barbier-Mueller museums in Barcelona and Cape Town.

Museu Barbier-Mueller d’art precolombí, Barcelona

The Barbier-Mueller collections of pre-Columbian art, after being successfully exhibited in a number of museums in Spain and Portugal, were lent on a long-term basis to the municipality of Barcelona in 1997. Until 2013, they would be displayed at the Museu Barbier-Mueller d’Art Precolombí, installed in a palatial hall provided by the municipality of Barcelona and located opposite the Museu Picasso.

Gold of Africa Barbier-Mueller Museum, Cape Town

In 2003 the Gold of Africa Barbier-Mueller Museum was inaugurated in Cape Town, with displays of gold ornaments and jewellery from Ghana, Côte d’Ivoire and Mali, under the management of Anglogold. This museum was accessible to the public for ten years.

The richness of the Barbier-Mueller collections has allowed the museum to organize over ninety exhibitions within its walls and nearly a hundred throughout the world, over the more than forty-five years of its existence. Most originated in collaboration with researchers, and others blossomed thanks to dialogues that poets and artists entered into with the museum pieces.